Anna Almore is an inspiring educator who works in teacher development here in South Texas. In addition to being a thoughtful person and friend, Anna is doing exciting work here encouraging teachers to reflect deeply on their vision for their classrooms. I saw an early version of this post in a regional newsletter and thought it was one of the best things I have read on teaching Black History Month. Enjoy the read and thank you Anna!

In 1926, historian, philosopher, and scholar Carter G. Woodson declared the second week of February as “Negro History Week.” With the birthday of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass falling in that second week, it was only appropriate to celebrate a history systematically left out of curriculum and national consciousness would occur when the nation was celebrating the lives of two freedom fighters. Woodson’s original intent was that this week would no longer need to exist when Black History was justly represented in the story of America.

93 years later, I am pushed to consider two questions: Why does Black History month still matter and why does Black History month matter down here in the Rio Grande Valley?

To me, Black History month is one way we as a nation can commit to the study and celebration of a history of change. A history of freedom, equality, and justice denied. A history of oppression and opportunity. A history of contradictions and compromise. A history of the pursuit of the American dream. A history of this American dream deferred. This history seems to embody the American spirit and power that Margaret Meade famously stated in these words: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed, citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.”

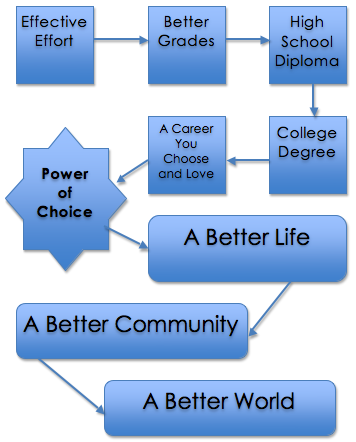

This story of change is what compels me to study and celebrate Black History down here on the Mexico-US border. Our community has much to celebrate—increased graduation rates, the opening of new early college academies, drop in unemployment rates—but we are still in need of change. With 91% of the population in the RGV identifying as Hispanic, there is only a 12% likelihood of earning a college degree six years out of high school according to our most recent Census data. This compounded with the plight of the Colonias, aggressive patrolling on the border, a heated immigration debate, a widening gap between the “haves” and “have nots”, and policies that deny medical and essential care to the elderly, disabled, and disadvantaged—the pain of our community is real. This pain is what connects me to Black History, and it’s the promise and hope embodied in this history that makes me study it. The lessons of leadership, community, and love are as relevant today as they were then.

What makes celebrating Black History difficult is that we must embrace and walk through the pain in order to squeeze out the universal lessons of Black history. This process of self-scrutiny, national-analysis, and historic-criticism requires us to deal with the complicated issues of race, class, trauma, hatred, and violence. How does an educator, especially one that does not share the racial background of his or her students, go about doing this? The first step, like any painful path, is having the courage to admit and name the truth of trials and victories of Black history. Once we can honestly do this, the rest comes more naturally.

Once you admit the reality and relevance of Black history, then we must turn to ownership. Why do you care about Black history and what is your point of entry into this particular narrative and tradition? Consider this list:

- Your decision to join the legacy of education in America

- The potential of Brown v. Board of Education

- The power of youth embodied by the Freedom Riders and Sit-In organizers of the South

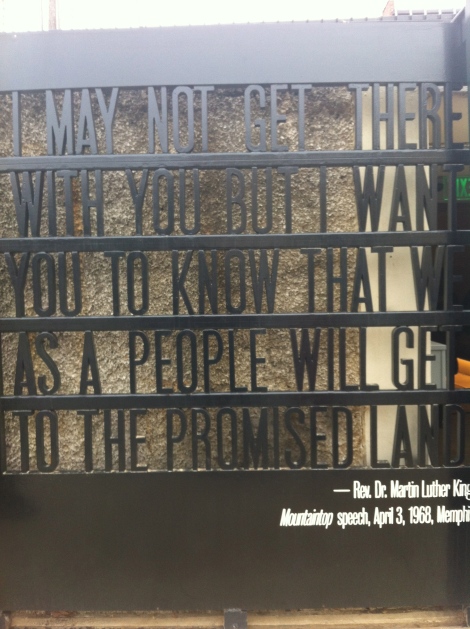

- Your belief in MLK’s dream

- A commitment to earning the title of “Ally” to communities in need

- The story of Allies who sacrificed their privilege to empower others

- Your deep friendship with and connection to Black people here, in your schools, or at home

- A fierce patriotism and desire to see the American dream realized

- The music, culture, stories, and values of Black people

- The universalism of this story

- Your faith and its power to move mountains

- Last but not least, maybe you are celebrating Black History Month because you are the living example of Black History, a testament to why the fight and struggle was necessary, a person who’s traditions are steeped with justice, equity, and love—you are a Black person living in America today

Whatever your reason is, the next piece of the equation is courage—mustering the courage to share this tradition through your content, stories or media with students. In doing this, it’s imperative to name here that you will without a doubt open up a world of dialogue in your classroom that will undoubtedly be good for kids but also certainly difficult. Here is some advice I’ve compiled recently and over the years to navigate these sometimes awkward, full of mistakes and misteps, but totally worth it conversations:

- Don’t get weird about it: if a student says something inappropriate, recognize that it often comes from a lack of knowledge or what they have seen in the media. Address it immediately, unemotionally, and follow up with a one-on-one conference. If a consequence is necessary, use it. If other students can redirect the conversation—let them.

- Use words wisely: Preemptively permit students to use the words “Black” and “African-American.” Redirect kids who use the word “racism” incorrectly by sharing the definition. Have your Webster’s dictionary readily available to shut that conversation down.

- From my favorite high school English teacher on the planet: “And, let me acknowledge that some of you are inevitably wondering or doubting yourself about the acceptable language here for talking about race, so let me give you two options: ‘black or African American’ Now, you might find other language used, even by people writing about Brooks during her own early years that uses language that was common or acceptable then but that is considered anywhere from archaic to offense today (see me if you need or want to check on examples), so to eliminate any doubt, I’m telling you to say black or African American. And, let me also be clear that you should not say these words with a whisper or drop in your voice, because even if doing so is a result of your own uncertainty about using the correct terminology, the act of doing it seems offensive, as if it is wrong to identify as or say the word black.”

- Add these questions to your bank:

- How do you know that to be true?

- What are other people’s opinion?

- How does this connect to the history of the Valley?

- Are you trying to say…?

- Is that based on fact or from a stereotype?

- Where are you getting this opinion from—TV, media, film, internet, music?

- Embrace what you don’t know: if your students ask a question that you don’t know the answer to, embrace the phrase “I don’t know but that is a great question.” Encourage students to research their questions or commit to writing down their questions and doing your own.

- Encourage connections: help your students find similarity and overlap in the stories of Black Americans. Show your students how you SEE yourself in this history and they will follow!

- Commit to consistency: reducing BHM to one day, one quick conversation reduces the potential impact and perpetuates the idea that you can celebrate and commemorate a legacy of an entire people in one day

- Acknowledge reality: there are not a lot of Black people in the Valley and that’s why talking about matters. It’s also why your students experience may be limited to TV, film, the news, and internet. Be sure to name that.

- Keep stereotype at the forefront of your mind: share the definition of stereotype and address instances of stereotype objectively, immediately, and with love. Constantly ask, how might what we are saying add to or take away from stereotypes? Commit to destabilizing your students’ stereotypes.

- Commit to keeping the conversation going: don’t let February 28 be the cut off for great, deep conversations! Keep the momentum going and honor the legacy of Black people, Carter G. Woodson, and others by not letting it die the last day of February.

- Check out this book: http://www.amazon.com/Other-Side-Jacqueline-Woodson/dp/0399231161

How are you celebrating Black History Month? Leave your suggestions and ideas in the comments section!